Music from the Carpathian Bow

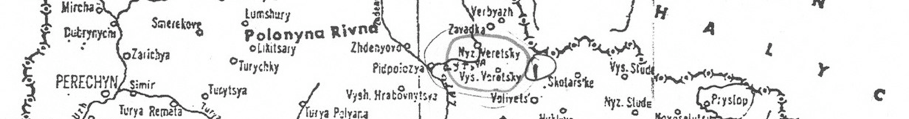

I made my debut on December 22, 1921, in a village by the name of Nizhni Verecky, population about 3,000. Our town was nestled in the mountains of Sub-Carpathian Ruthenia, a province of Czechoslovakia. Ours was a picturesque, pristine country, with majestic mountains, some of which were snow-capped all through the year, crystal clear water in the rivers and streams, lush green meadows, and dense forests covering large areas. The air was fresh (unpolluted) and invigorating. As to the climate, the winters were quite cold with deep snow covering the ground from about November to about April, a season of fun from which most of my pleasant memories emanate, such as sledding, skiing and riding to school on skis hitched to horse-drawn sleighs, which occasionally resulted in being whipped by the peasant, but it still was fun. Spring was cool but pleasant. May was the month of renaissance, when nature emerged from slumber and burst out in a brilliant display of color. I can still recall the intoxicating fragrance of the Lily of the Valley that grew on the meadows and of the lilac blooming in front of the homes on the main street. I liked the smell of the freshly ploughed earth, of the grass and of the freshly cut hay later on in the summer. I didn't even mind the smell of horse manure or cow dung on the streets. The summers were also delightful, warm, but not hot, days and cool nights with good sleeping weather. Day-time temperatures ranged between 60 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit with practically no humidity. It was considered a heat wave when it occasionally got up to 75° F.

Life in Verecky was rustic, simple, unsophisticated. No electricity or plumbing. Instead of indoor toilets there were outhouses. Of course, there were no bathrooms. We did go to the "mikveh" (communal bath) once a week. At other times we had to go to the river to wash the upper part of the body (summer or winter). Naturally, there were no washing machines. The wash was done by hand. Although there were no refrigerators, the food didn't spoil as it didn't last long enough to decay.

The train station was 7.5 miles away and transportation to it was provided by horse-drawn vehicles as well as by one bus and taxi we had in our town. Bicycles were also used quite frequently. The only telephones in town were in the gendarme station, in a few of the town administration offices and in the post office, which was the only one accessible to the public.

Only the main street was paved. All the side streets were just trodden paths. Many of the homes (including my grandparents') had thatched roofs.

Ruthenians (of Ukrainian stock) made up the majority of the population. Most of them were farmers. While some of them were well-off, quite a few lived in poverty. Some raised cattle although not on a very large scale as in the U.S. One of them (quite wealthy) owned a large department store, a tavern and restaurant. Another (also well to do) owned a tavern. One had a

butcher shop and one was a black-smith. Only a small number of the Ruthenians lived along the main street. The rest lived along the side streets. Most of them were dressed in garments of home-spun, coarse material.

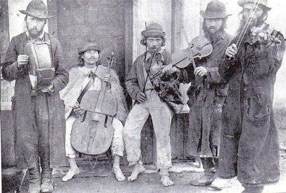

Musicians in Verecky, probably Gypsies

Czechs comprised the next ethnic group in numbers. Those were the government administrators, gendarmes, border guards and school teachers. There was also one Czech butcher, a judge and a prison warden.

There lived several Hungarians in Verecky. One was a physician (who was seldom sober in fact he died before his time of an alcohol-related illness), one pharmacist, the only one in town, one black-smith and one chimney sweep. We had one solitary gypsy who had lost his wander-lust. He lived in an old broken down shack at the eage of town. When he wasn't busy cleaning outhouses he played the violin to augment his pitiful earnings.

Itinerant gypsies would visit our village from time to time and that caused considerable panic among children, especially the unruly ones, who took seriously the warning that if they didn't behave, the gypsies would kidnap them.

Kansas City August 29, 1993

To my dear children and grandchildren. This is my legacy to you. This is the story of my life. All my experiences still preserved in my memory through the mists of time. There are certain passages here that don't make for pleasant reading the pain of which I would have liked to spare you. I feel, however, I owe you an account of all my experiences, the good as well as the unpleasant.

With all my love, Dad / Grandpa

Memoirs

Boris Segelstein